Learning the Art of Falconry

Joby Sabol and OZ, a red-tailed hawk demonstrate their teamwork on Sabol’s property off Bridger Road near Bozeman last winter.

BY BRYCE LEDBETTER AND STAFF

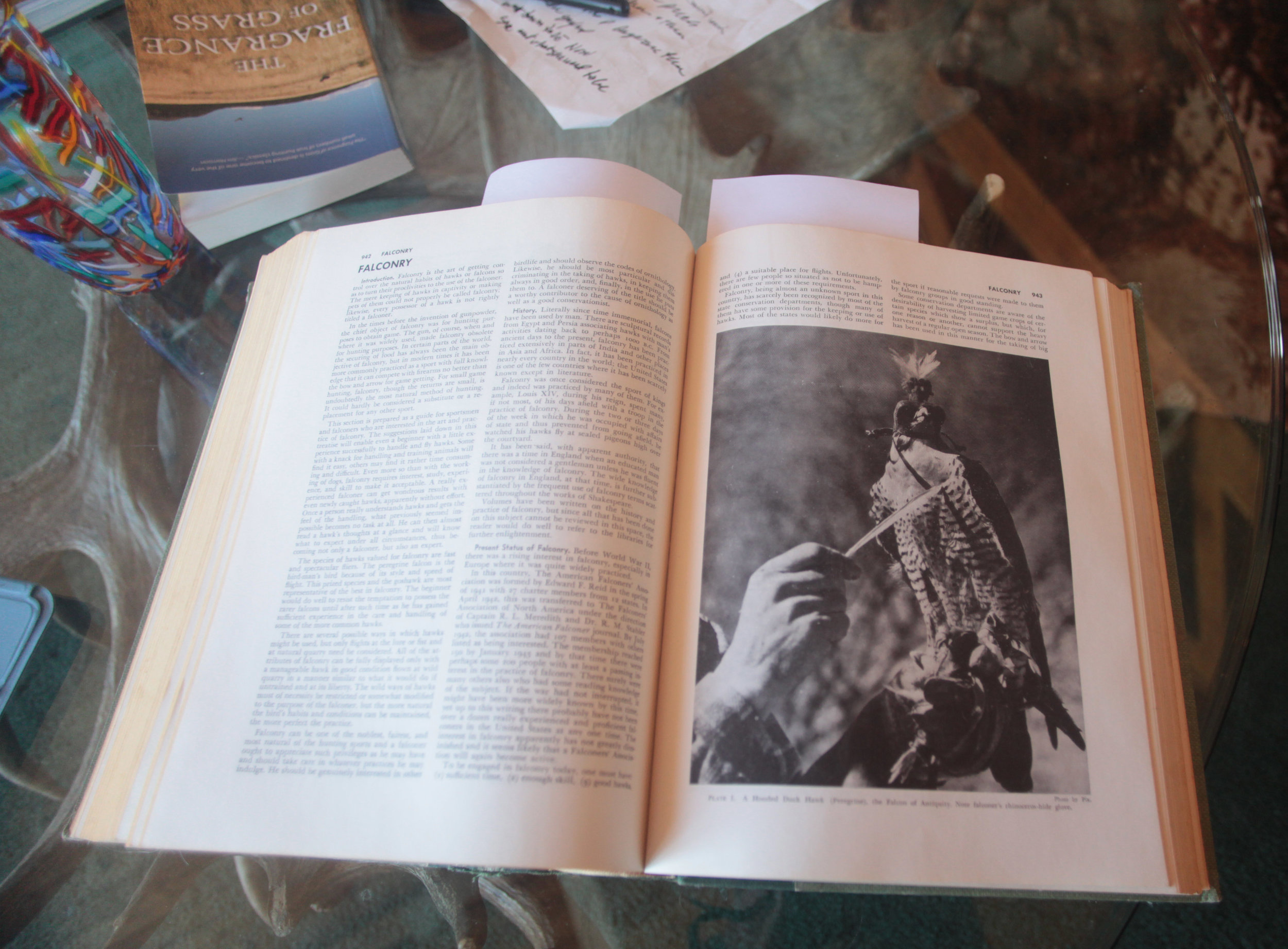

Joby Sabol caught the falconry bug at an early age. “I was struck by this book my father had when I was six or seven,” he recalls. The book, The New Hunters Encyclopedia that originally piqued his interest is long lost. Only recently did he find another copy of the book on Amazon. It’s cover is slightly worn and he handles it as if it were a precious relic that belonged behind thick glass in a museum display. “This was my first introduction to falconry,” Sabol said, “the only two things I remembered in this book were the pictures from a falconry story and this series of pictures of a high powered bullet going through a block of Jello.”

Sabol often thought about those images in his fathers book but his own duties as a husband, father and a successful law practice meant that his childhood dream of falconry would have to be put on the back burner. “There was just no way I was going to be able to take the time and energy it took to be successful.”

Recently Sabol was hit hard with the bug again. Now his kids are grown and out of the house, and with a new career in ranch management, Joby found he had a little more time on his hands. “Wow, I’m finally in a place and a position in my life that I could do it,” he exclaims to himself.

Getting started, however, was not easy. “To get into falconry you have to take a fairly substantial exam. You have to build a birdhouse that must be inspected by Montana FWP. Then you have to practice under a master falconer for two years.” It’s an arduous and time-consuming process. As with so many things, the sport is strictly regulated by the government. “They (the feds) have set the bar pretty high and not many people want to suffer through that.”

The art of falconry dates back to 2,000 BC where records indicate that raptors were used to hunt in ancient China. In Arabia and Persia in 1700 BC pictorial records and wall hangings show falconers with birds on their wrists.

Falconry reached great popularity in Medieval Europe between 500 and 1500 and was very popular up until the time of the French Revolution in the late 18th century. Images of a medieval Lord traveling through an English forest in search of wild game comes to mind. The falcon would have been a constant companion in these traveling bands. During the reign of King Edward III, 1327-77, theft of a trained raptor was punishable by death.

Nowadays the sport of falconry is alive and thriving.

In The New Hunters Encyclopedia the first paragraph of the introduction to falconry states that falconry is the art of getting control over the natural habits of hawks or falcons so as to turn their proclivities to the use of the falconer.

The Montana Fish, Wildlife & Parks offical website also states: It is unlawful for any person to possess a raptor or to train a raptor in the practice of falconry without either a falconry license or a raptor propagation license. Raptor means all birds of the orders falconiformes and strigiformes, commonly called falcons, hawks, eagles, ospreys, and owls.

“There really aren’t a lot of people rushing to get into this sport because the bar is set pretty high on what you have to do. Between the test and the inspection and the apprenticeship not may people want to suffer that,” Sabol laughed.

He took the exam a year ago in March, built his birdhouse over the summer and trapped a red-tailed hawk he named OZ the first week of August near Big Timber. And in three months the two seemed to be getting along just fine.

“I trapped my first red tail just back in August. OZ is a red-tailed hawk that Sabol caught by using a small wire box and some netting with a mouse inside. “You drive down the road till you see the hawk you’re looking for up in a tree and then drop off the box and you’re off to the races. A lot of people start with red tails, they’re kind of the Labradors of the raptor world. Their bodies are a little bit bigger and easier to manage their weight.”

Like a prize fighter, everything with falconry is based on weight. Sabol weighs OZ every morning and every evening. Too heavy and OZ can’t navigate the obstacles that are thrown his way. Also, Sabol explains that if you feed them too much they won’t really want to hunt. “He’ll just sit up in his tree fat and happy. With the help of your master you determine what that flying weight is.”

In mid-November on a bitter cold but sunny day with a deep blue sky overhead Joby and OZ emerged from the birdhouse and set out to give us a sneak peak into the world of falconry.

Sabol releases OZ into the air and the hawk flew to the top of a tree on Sabol’s property. Then Sabol gives a call and OZ leaves his perch high above the ground to swoop back onto Sabol’s glove. You quickly see Oz’s natural hunting prowess as he flies around Sabol’s property demonstrating his speed and agility.

“The birds are very smart and that bird associates me as a food source or food provider. He knows that if he hangs around me he’s going to get feed one way or the other. Either I’m going to get him into a rabbit or a pheasant that he can take down or he can eat off of my glove or a little of both.” It only took about a month for Sabol to train OZ to come back to him.

“He is wild. And the goal is to never turn him into a pet or never to tame him. Really the whole adventure of falconry is that bird kind of putting up with me and allowing me to be a part of his world and go out with him to hunt alongside of him and watch him take game. He tolerates me more than anything.”

“I got lucky. My bird is very docile and very easy going. Relative to other birds he’s easy to get along with. He’s a great first bird. I mean it’s a lot more about training me than it is about training the bird at this point.”

Sabol says he will have this bird for a year and half to two years and then turn him loose back into the wild. Then he’ll go get another bird, probably a different species, so that he gets experience as an apprentice conditioning and manning different types of birds.

For now Joby and OZ are enjoying the ancient sport of falconry admits the natural beauty of Montana. If you would like more information about the sport, please visit Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks (fwp.mt.gov).